Takeaways (without the BS)

The Jones Act does more harm than good.

The Jones Act should be repealed. At a minimum, Puerto Rico (and other islands) should be fully exempt from its burden.

Even if you don’t want to repeal the whole thing or exempt Puerto Rico, the Jones Act should automatically be suspended during states of emergency, such as hurricanes.

What is the Jones Act?

Here, I’m primarily interested in one part of the Jones Act, which is itself part of the larger Merchant Marine Act of 1920.1 The salient piece I want to discuss is: to move goods from one U.S. port to another via water requires the ship be made in the U.S., flying a U.S. flag, and crewed by U.S. citizens.2 The stated intention is to ensure the U.S. retains adequate shipbuilding (and maintenance) capacity — essentially a national security argument.3

I believe the costs far outweigh the benefits. An early study estimated the annual costs be around $2 - $3.4 billion (this would be about $7-$8 billion today).4 A more recent study suggests the cost differential to build a Jones Act-compliant ship is around $60-$75 million per ship, plus an additional $1 billion annually in labor costs [A helpful reader points out that this is a low estimate because a recent Jones Act ship costs about $225 million to build while one built overseas costs less than $50 million]. Other analyses have proved more challenging. For example, this excerpt from McMahon (2018).5

According to the GAO [Government Accountability Office], they “collected and analyzed data, reviewed literature and reports relevant to these markets and gathered the perspectives and experiences from numerous public and private sector sources…

…However, because so many other factors besides the Jones Act affect rates, it is difficult to isolate the exact extent to which freight rates between the United States and Puerto Rico are affected by the Jones Act.

While the GAO's audit produced no evidence that Jones Act shipping rates to Puerto Rico were more expensive than those that foreign carriers would charge…

[p. 160]

In that last sentence the author seems to confuse “no evidence” with evidence of absence — not the same thing. The GAO simply said it’s really hard to disentangle the effects specific to the Jones Act. They did not say the Jones Act imposed no additional costs relative to a world where the Jones Act didn’t exist. The earlier studies I mentioned actually shows the opposite — the Jones Act is very costly.

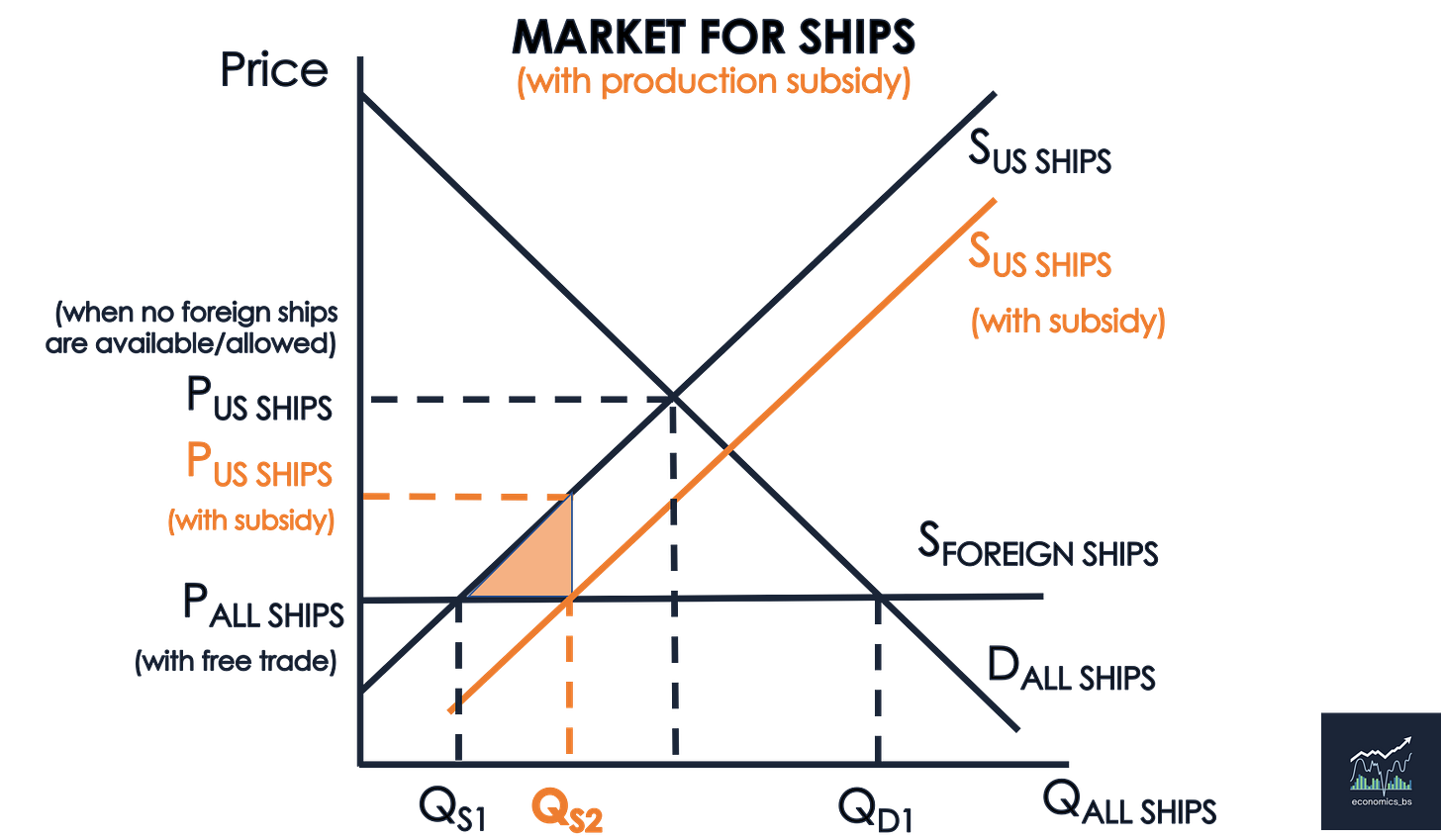

Maybe this is my bias as an economist, but if you really value the shipbuilding industry then just…subsidize it. Provide incentives in the form of direct subsidies (or tax breaks, if you think that sounds better) for shipbuilders to ensure the U.S. maintains whatever capacity it deems necessary. Do not cloak your coddling of the shipbuilding industry in obscure rules that prevent critical goods from reaching places like Puerto Rico in times of distress. Directly subsidizing the industry would spread the cost across more taxpayers, solve the access issues that are particularly harmful when we can least afford them (such as during a hurricane6), and would be less costly/distortionary overall to consumers. I try not to do this too often, but if you’ll indulge me for a couple of minutes, I think two graphs might help illustrate my point: (1) tariff and (2) domestic production subsidy.

How is the Jones Act similar to a tariff?

If the problem you are worried about is national security — we need to keep producing ships so that we don’t forget how and so we can produce them in a hurry if needed (i.e. war) — then you essentially want to increase domestic supply. How do you do that? Incentives. Shipbuilders respond to incentives like everyone else. If you (policymaker) want them (shipbuilders) to make more, then you might need to help them get a higher price for their product.

Tariffs can help achieve this.

In this diagram (above), we first see that the price of US-made ships is much higher than the price for all ships. When there is no trade, US shipbuilders are able to charge a high price and production of US ships is high. When there is free trade, ship buyers are able to purchase foreign ships for a much lower price (Price of all ships), so many US shipbuilders are forced out of business as domestic supply is reduced down from

Q w/out trade to QS1. This is where the Jones Act comes in. The intent of the Jones Act is to reduce consumption of foreign ships and increase consumption — and, by extension, production — of US ships from QS1 to QS2. However, to do this effectively, the price for US ships has to rise.7 This is the incentive shipbuilders need to increase production. There are two problems with doing this. First, the green-shaded triangles represent deadweight loss: areas that used to be consumer surplus8 and now go to no one. These areas represent lost benefits to the U.S. Second, the total amount of ships purchased decreases from QD1 to QD2. This is problematic because now there are less ships available at crucial times, such has during natural disasters.

Below, the government uses a domestic production subsidy instead. The government would just send checks to shipbuilders for each ship they build and sell. This helps them reach a higher price but, importantly, without distorting the price consumers pay for the ships. In other words, companies that buy boats still get the world price (Price of all ships with free trade), so the total number of boats purchased is unchanged at QD1.

If we place the graph side-by-side, you can clearly see the subsidy case (right) is less harmful because there are less shaded areas. This is because the subsidy does not distort the price consumers pay for ships, which means shipping rates are equal regardless of the producer of the vessel.

There are lots of caveats to this strategy: Do you give subsidies to all producers? If not, how do you determine which producers are the best? In other words, how do you make sure you are not subsidizing an inefficient producer?] However, it at least offers the possibility of being more efficient than a tariff while still achieving the alleged national security goals.

Tl;dr — get rid of the Jones Act; it’s antiquated and does more harm than good.

The latter involves many other areas, including treatment of the crew, which I do not address here. Everything in the act is worth discussing, but that is outside the scope of what I want to discuss here.

You can read much more here from the Cato Institute. Keep in mind that Cato is a libertarian think-tank.

Francois, J. F., Arce, H. M., Reinert, K. A., & Flynn, J. E. (1996). Commercial policy and the domestic carrying trade. Canadian Journal of Economics, 181-198.

McMahon, C. J. (2018). Double down on the Jones Act. J. Mar. L. & Com., 49, 153.

Waivers are sometimes granted during hurricanes, but it seems senseless to even have to go through this process during a time of such high need.

Here, I assume the price of foreign ships is below that of US ships. This is a reasonable assumption because the Jones Act would not have been instituted initially if US shipbuilders were already competitive with their foreign counterparts.

We generally define consumer surplus as the area above the price and below the demand curve — the difference between what you actually pay and what you’re willing to pay. For example, if you are willing to pay $9 for a cup of coffee but the coffeeshop only charges you $4 for a cup, then that transaction creates $5 of consumer surplus.