FED: Will there be a soft landing or are they going to overshoot the runway?

Tune in for more aviation metaphors!

Takeaways (without the BS)

A soft landing — i.e. no recession — is unlikely.

A hard landing — Great Recession-style — also seems unlikely, with the salient caveat that there could be unforeseen changes in world events (disease, war, etc.)

Aviation metaphors aside, there will almost certainly be a recession at some point over the next two years, whether that is because of sustained higher inflation, rising unemployment, or *gulp* both. The open question is: how severe will it be?

What might cause a recession?

First, let’s define recession. You may have a heard a recession means two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. That’s wrong. The Fed generally looks for declining economic activity that exhibits “depth, diffusion, and duration.” The Sahm Rule predicts whether we are currently in a recession and it, too, suggests the answer is no. So, we are not yet in a recession, despite crossing the mark of two consecutive quarters of GDP decline.

The Fed has two jobs: maximum employment and stable prices. This is known commonly as the dual mandate. It essentially means the Fed tries to guide the economy to low, stable prices and a low unemployment rate. So, failing to achieve one or both of these for an extended period and for a significant portion of people, can mean we have a recession. The paradox is that pursuing one goal can detract from progress on the other.1 Currently, inflation is very high in the United States at 8.3% for overall CPI and 6.3% for core CPI (which removes the historically volatile measures of food and energy). The Fed usually follows the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price index more closely. Its readings sit at 6.2% for overall and 4.9% for core PCE prices. Virtually all measures of inflation are high and core measures of inflation have been stubbornly persistent. Bringing inflation back to something more stable requires decreasing economic activity, which means the unemployment rate will almost certainly have to rise.

Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell recently announced the Fed will hike rates an additional 75 basis points (0.75 percentage points), the fifth increase this year and the third consecutive increase of 75 basis points. The Fed also released its summary of economic projections — note that their median projection for core PCE for 2022 is 4.5%. We are currently trending about a half percentage point above that with only minimal signs of slowing down. This means the Fed is likely to stay the course with its aggressive rate hikes and all that entails (housing market, financial markets, etc. are harmed by this). Indeed, median projections suggest the federal funds rate will remain above 4% for the next two years, a further indication that policymakers are worried about inflation persistence.

There have been additional developments across the pond, as the ECB raised its base rate from 0% to 0.75%, the first increase in over a decade. This should help put downward pressure on inflation in the U.S. as well. Why? The stuff we buy from Europe should get cheaper as inflation there comes down. In the meantime, higher interest rates abroad should decrease economic activity in Europe, and this lower demand will also put downward pressure on U.S. (export) prices.

Wait. If European and American consumers are buying less stuff, might that cause a global recession? Yes! That is part of the Fed’s (and other central banks’) dilemma. Bringing inflation down means reducing economic activity. Other countries are also dealing with high inflation. The faster countries raise interest rates, the more the Fed’s own policy is amplified.

Ok, so now what? The Fed has an extremely difficult job because there are so many moving parts in the economy, all of which appear to respond and change at differing rates. Imagine it like this: the Fed is trying to land this plan softly, but it’s extremely foggy outside and some of their instruments have not been working properly. Landing softly when you can only see pieces of the runway at uneven intervals makes the task very challenging. We are in for a bumpy ride, as we’ve already seen in the stock market and are beginning to see in the housing market.

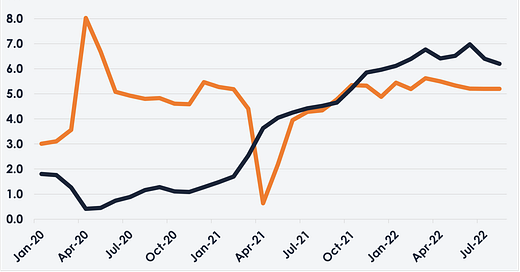

One particularly challenging piece of the inflation puzzle is wage growth. Currently, nominal wages are growing at a relatively fast speed (orange line) but prices are rising faster (dark blue line).2 We generally like to see nominal wages increase faster than inflation. This results in what we call real wage growth, which means that people’s purchasing power is growing. Right now we have the opposite scenario — even though people are earning more money, the stuff they buy is increasing in price even faster. This risks a wage-inflation spiral: rising prices causes workers to demand higher wages, which force firms to raise prices more to cover the cost of higher wages, which leads workers to demand higher wages, which…you get the idea. This is a tough pattern to break. To do so, the Fed will need to re-anchor inflation expectations. That is, people need to believe that prices will stop rising so quickly, so they stop asking for ever higher raises, so that firms can slow down price increases. The quicker the Fed does this, the smoother will be the landing for the economy.

Other News:

I’m not sure what the new UK government is thinking, but tax cuts right now would add fuel to the inflation fire already raging across the world. The Bank of England was forced to step in and try to counter the insane move, but it’s unclear whether it will be enough. The pound seems to have recovered but I assume there are more rocky waters ahead.

Gross Domestic Income and Gross Domestic Product were revised, bringing the two closer together. In theory, they should be equal but differing data sources often leads to small discrepancies. Until the most recent revision the gap between them had widened. GDI still shows economic growth in the first half of the year while GDP shows the economy shrank. Economists tend to prefer the average of the two, which was slightly negative for each of the first two quarters.

Check this out from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank. The article discusses the relationship between inflation and unemployment, and how that relationship can change over time under varying economic circumstances.

Wage data are average hourly earnings of all employees and the price data are Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Price Index.